Why the AI Revolution Is Not a Dire Threat to Employment

According to some estimates, 30% of current U.S. jobs could be automated by 2030 nu.edu. That statistic sounds alarming, fueling fears that artificial intelligence (AI) will leave millions unemployed. Such concerns are understandable and not new. In fact, nearly every technological revolution has sparked worries of mass job loss, from 19th-century textile machines to 20th-century computers. History, however, tells a different story: while new technologies do disrupt and even eliminate certain jobs, they also create new industries and roles, often leading to more employment overall, not less mckinsey.commckinsey.com. In an optimistic and evidence-based view, the AI revolution is poised to transform jobs rather than simply destroy them, much like past innovations ultimately increased opportunities and improved work for many people.

Historical Parallels: From Blacksmiths to Mechanics

During the Industrial Revolution, traditional craftsmen saw their roles profoundly change. A classic example is the village blacksmith, once essential for forging tools and shoeing horses. As factories and automobiles emerged, the need for blacksmiths dwindled. Many blacksmiths transitioned into the first generation of automobile mechanics when horses gave way to cars oldwestiron.com. In other words, old jobs were replaced by new ones. This pattern is a prime illustration of economist Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction,” where innovation may eliminate some occupations but simultaneously creates new industries and employment opportunities weforum.org. For instance, the rise of automobiles in the early 20th century wiped out many horse-related jobs (like carriage makers and stable hands) yet spawned entirely new sectors: auto manufacturing, mechanic workshops, gas stations, road construction, motels, and more mckinsey.com. Far from collapsing, the labor market adapted. Overall employment kept rising in industrializing countries even as certain jobs vanished, thanks to higher productivity, new products, and greater demand for services mckinsey.commckinsey.com.

Another striking historical shift was the decline of agricultural work. In 1790, about 90% of Americans worked on farms; today it’s less than 2% humanprogress.org. Mechanization and modern farming dramatically reduced the need for farm labor. Yet those displaced agricultural workers did not remain idle, they moved into manufacturing and later into service and tech jobs. By the mid-20th century, manufacturing absorbed millions (peaking at ~38% of U.S. jobs in the 1940s), and by the 2000s the service sector dominated employment humanprogress.org. Each economic era saw old categories of work fade but new ones surge in their place, from factory assembly lines to clerical office work to today’s software development and healthcare roles. The lesson is clear: society has weathered big job transitions before. Technology changed what work people do, not whether people work. Employment as a whole has grown over time despite periodic fears, because innovations increase productivity, lower costs, and spark new demand that employs people in ways previous generations could barely imagine mckinsey.commckinsey.com.

The Digital Revolution: From Mail Carriers to Web Designers

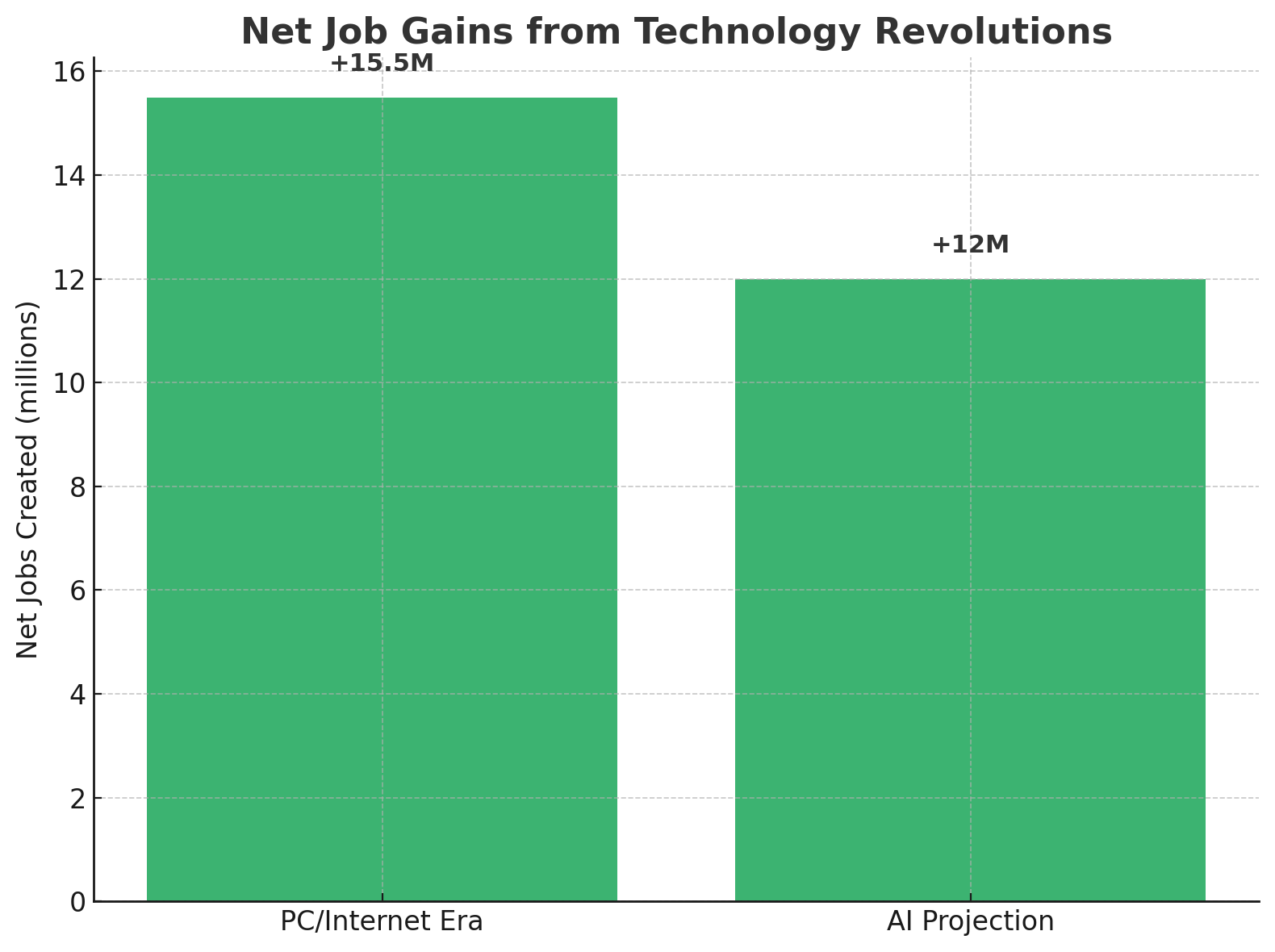

Fast-forward to the late 20th century, the era of computers, the internet, and automation. We saw a similar story play out. Personal computers and software eliminated millions of routine office jobs (think of typists, switchboard operators, and filing clerks). For example, executives no longer needed secretaries to take dictation and type memos once email and word processors arrived. Indeed, one detailed analysis found that from 1980 to the present, the rise of PCs and the internet “destroyed” about 3.5 million U.S. jobs in office administration, accounting, and similar roles mckinsey.com. But in that same period, 19 million new jobs were created in industries that didn’t exist before, from IT support and software development to online customer service and digital design, yielding a net gain of roughly 15 million jobs attributable to the computer age mckinsey.commckinsey.com. In other words, the digital revolution didn’t put everyone out of work; it shifted workers into new, often higher-skilled jobs (many of which pay better and are more engaging than the repetitive tasks they replaced).

We can see this clearly in how the internet transformed communications. Traditional mail volumes declined as email and messaging grew, contributing to a steady drop in postal service jobs (the U.S. Postal Service is projected to shrink its workforce by about 28% over a decade) foxbusiness.com. Yet, the internet simultaneously gave rise to entire new career fields unimaginable decades prior, web designers, software engineers, digital marketers, IT technicians, online content creators, and more. A generation ago, “web developer” or “SEO specialist” were not job titles; today hundreds of thousands are employed in these occupations. In fact, a recent report estimates about 10% of the U.S. labor force works in jobs that largely owe their existence to the personal computer and internet boom of the past few decades mckinsey.com. The pattern from history repeated: old roles like file clerks or mail sorters declined, but tech innovation opened new avenues of employment. Even the very tool fueling anxiety, AI, is creating jobs already. The World Economic Forum projected in 2020 that by 2025, AI would create 12 million more jobs globally than it displaced blog.investengine.com, as organizations invest in new technologies and need workers to implement and manage them. While such forecasts can change, the overarching trend is that technology transitions are accompanied by job creation in emerging fields, often outpacing the losses in old fields over time.

Jobs AI Might Replace (and Why It’s Not Doom)

AI and automation will undoubtedly disrupt certain jobs, especially those centered on repetitive, predictable tasks. Some categories of work that analysts consider most at risk include:

- Clerical and administrative roles: Secretaries, typists, data entry clerks and similar positions are highly automatable. Many of these routine office tasks can be handled by software or AI, and indeed such roles have been steadily declining mckinsey.comnu.edu.

- Retail cashiers and bank tellers: Self-checkout kiosks and ATMs/digital banking services are reducing demand for these jobs. For example, U.S. bank teller employment is projected to decline ~15% by 2033 (about 51,000 fewer teller jobs), and cashier positions by about 11% (over 350,000 jobs lost) as automation expands in stores nu.edu.

- Manufacturing and assembly line jobs: Factory robots have been replacing routine assembly tasks for decades. Since 2000, automation contributed to the loss of around 1.7 million U.S. manufacturing jobs nu.edunu.edu. AI-powered machines can perform welding, painting, packing, and quality inspection with increasing efficiency.

- Customer service and telemarketing: AI chatbots and voice assistants can handle basic customer inquiries and cold calls. Companies are already using AI customer support agents to supplement or replace human call center workers nu.edu. Jobs like telemarketer and entry-level customer service rep are expected to keep declining as these AI tools improve.

- Transportation (long-term): Self-driving vehicle technology targets jobs like truck, taxi, and delivery drivers. While full autonomy is still being tested, its future impact could be significant.

It’s important to stress that even in these areas, job loss won’t happen overnight. Historically, automation is adopted gradually, and many roles evolve rather than vanish instantly. Take the example of autonomous vehicles: even if perfect self-driving cars were available today, experts note it would take over two decades to fully replace the global fleet of human-driven vehicles voxdev.org. During that transition, new types of jobs would appear, for instance, overseeing autonomous fleets, maintaining sophisticated robotic trucks, or providing services in an economy where transportation is cheaper. Additionally, AI often automates tasks within jobs more than entire occupations. A bank teller’s role, for example, has shifted to focus more on customer relationships and complex services as ATMs took over simple cash withdrawals. Humans and machines will collaborate, with AI handling routine elements while people focus on the interpersonal, creative, and complex aspects of work that technology still struggles with. This task-level transformation can make many jobs more interesting and productive rather than redundant.

Crucially, economic growth fueled by AI can create demand that absorbs workers elsewhere. When productivity rises, the cost of goods and services falls, and people tend to consume more or new things, which in turn creates jobs. We’ve seen this “virtuous cycle” in every past revolution mckinsey.commckinsey.com. There is no finite lump of work to be divided; as AI boosts efficiency, it can expand the economy and generate new employment in ways that are hard to predict in advance mckinsey.commckinsey.com. The jobs of the future may not be immediately obvious, a reminder that in 1900, nobody could foresee jobs like “airplane pilot” or “software developer.” Likewise, new roles will emerge from AI that we can barely imagine today.

New Industries and Roles Emerging

If history is a guide, the AI age will not only disrupt jobs, it will also create entirely new professions and industries. In fact, this is already happening. A World Economic Forum study highlights three broad categories of new AI-driven work: “trainers,” “explainers,” and “sustainers.” Trainers are people who develop and teach AI systems (from machine learning engineers to data scientists); explainers help bridge AI and human users (for example, designers who create user-friendly AI interfaces); sustainers ensure AI systems are used responsibly and effectively (such as AI ethicists and safety managers) weforum.orgweforum.org. Put more simply, AI is spawning demand for roles that didn’t exist a few years ago. One report notes the rise of job titles like “AI trainer,” “AI ethicist,” “AI explainability specialist,” and “prompt engineer,” which were virtually unheard of before nu.edu. Below are a few of the emerging careers in the AI era:

- AI/Data Scientists and Machine Learning Engineers: Experts who research, design, and build AI algorithms and models. As organizations race to deploy AI, these roles are among the fastest-growing, AI and data science specialists are seeing explosive demand in 2025 nu.edu.

- AI Trainers and Data Annotators: Humans are needed to train AI models by curating, labeling, and refining training data (for instance, reviewing AI outputs for accuracy or teaching an AI how to recognize certain patterns). These behind-the-scenes roles ensure AI systems learn correctly and ethically.

- Prompt Engineers and AI UX Designers: Specialists who craft the questions, prompts, and interfaces that help users get the best results from AI (especially relevant for generative AI like chatbots). They make AI tools more accessible and tailored to specific tasks.

- AI Ethicists and Safety Officers:** Professionals dedicated to making sure AI is fair, transparent, and aligned with human values. They develop guidelines to prevent biased or harmful AI outcomes and rigorously test systems for ethical issues. This category includes AI policy advisors, ethics researchers, and compliance managers, roles critical for responsible AI development weforum.org.

- Data Curators and Analysts: As AI’s appetite for high-quality data grows, so does the need for people to gather, clean, and interpret that data. Data curators ensure AI training datasets are accurate and unbiased weforum.org, while data analysts interpret AI-driven insights for business decisions.

Beyond these new titles, AI is also expanding traditional fields. For example, in healthcare, AI tools for diagnostics are augmenting (not replacing) doctors and radiologists, enabling the rise of specialists who manage AI-driven medical devices. In education, teachers are working alongside AI tutors and need training in “edtech” facilitation. Even trades like automotive repair are evolving, mechanics now often diagnose cars with AI-based systems. Entire new industries are being built on AI, from autonomous vehicle services to AI-driven agriculture, which will employ engineers, technicians, maintenance crews, customer support, and more. One encouraging statistic: despite all the doomsaying, the “jobs of tomorrow” related to AI are expected to far outnumber the jobs that AI makes obsolete blog.investengine.comblog.investengine.com. As of 2025, we already see millions of workers in AI-related occupations, and demand for these skills is only increasing. Fields like AI development, data analysis, cybersecurity, and robotics are growing rapidly, offering fresh career paths for the next generation nu.edunu.edu.

Adapting Through Education and Upskilling

The key to ensuring AI becomes a job creator (and not a widespread job killer) is adaptation, both by workers and by society at large. Past technological shifts teach us that investing in education, training, and reskilling is crucial. During the Industrial Revolution, many countries expanded public education so that factory workers could learn new skills. In today’s context, we are seeing what some call a “Skills Revolution” blog.investengine.com. As AI handles more routine tasks, the skills most in demand are shifting toward those that complement AI: digital literacy, data analysis, creative problem-solving, and the ability to work alongside intelligent machines blog.investengine.com. Workers who upgrade their skills, whether by learning data science, acquiring programming basics, or developing strong interpersonal and managerial skills that AI can’t mimic, will be better positioned in the evolving job market.

Encouragingly, many people and organizations are already responding. Companies are starting to provide AI training for employees (for example, training customer service staff to work with AI chatbots rather than be replaced by them). Governments and online platforms are offering courses in coding, machine learning, and digital skills to help workers transition. It’s estimated that around 20 million U.S. workers will transition to new careers or significantly update their skills to work with AI in the next 3,5 years nu.edu. This includes not only young professionals entering emerging fields but also mid-career workers pivoting from declining jobs (say, a truck driver learning to operate and monitor autonomous trucks, or a manufacturing worker retraining as a robotics technician). Society has a responsibility to support these transitions, through policies like retraining programs, lifelong learning incentives, and perhaps safety nets for those temporarily displaced. The good news is that, historically, workforces have proven resilient. Each new wave of technology initially caused turbulence in the labor market, but ultimately, employment levels recovered and even grew as people acquired new skills and moved into new occupations mckinsey.commckinsey.com. There’s nothing automatic about this, it requires effort and adaptation, but if we proactively prepare the workforce, AI can free humans from drudgery and open doors to more creative and fulfilling work.

Conclusion: History as a Guide to an AI-Powered Future

Every major innovation from the steam engine to electricity to the computer brought fears of widespread unemployment. And indeed, many job titles did disappear (we have few lamplighters, switchboard operators, or travel agents anymore). Yet, looking back, we see that human employment has not only persisted; it has continually reached new heights. The AI revolution, like the revolutions before it, is not a zero-sum game where machines’ gain is automatically humans’ loss. Instead, it’s an opportunity to redesign work and elevate humanity to the next level of productivity and innovation. AI will handle more of the repetitive and technical grind, while humans can focus on what we’re uniquely good at, creativity, empathy, complex decision-making, and interpersonal interaction. As MIT economist David Autor points out, the challenge and promise of AI is to enable more people to do more “expert” work with the help of smart tools, widening access to skilled jobs rather than narrowing it voxdev.orgvoxdev.org.

Of course, optimism doesn’t mean we ignore the real difficulties individuals face in job transitions. We must be realistic and compassionate about the disruption AI can cause for certain workers and communities, and work actively to mitigate it. Not everyone will find it easy to switch careers, and some gaps will require thoughtful policy solutions. But the overall evidence, from history, data, and current trends, suggests that AI will be a net job creator in the long run, as long as we make the necessary investments in people. The narrative of inevitable mass unemployment is too simplistic and pessimistic. A more likely future is one of job transformation: old roles evolving or giving way to new ones, the workweek reshaped, and productivity gains leading to new industries and maybe even shorter hours or more leisure for workers.

In summary, the AI revolution should be seen not as a harbinger of a jobless dystopia, but as the next chapter in a long story of innovation-driven progress. Just as the world adapted to factories, railroads, electricity, and the internet, we will adapt to intelligent machines. Societies that embrace education, agility, and forward-thinking policies will find that AI augments human capabilities rather than replacing them wholesale. The result can be an economy with more varied and interesting jobs, higher productivity, and prosperity that everyone can share, if we approach the transition with the optimism and preparedness that history urges us to have. As we stand on the cusp of this new era, the lesson is clear: don’t panic, but do prepare. The future of work with AI can be bright, and it will be shaped by the choices we make today. By learning from past revolutions and proactively managing the change, we can ensure that humans and AI thrive together in the workplace of tomorrow.

Sources: The analysis above is supported by historical data and expert studies, including insights from the McKinsey Global Institute on past technology impacts on jobs mckinsey.commckinsey.com, economic history of labor shifts humanprogress.orghumanprogress.org, projections from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on automation-vulnerable occupations nu.edu, and forward-looking research by organizations like the World Economic Forum highlighting new AI-driven roles weforum.orgnu.edu. These and other sources affirm that while AI will alter the job landscape, it need not spell disaster for employment, rather, if managed well, it can usher in a new wave of opportunities for the workforce.